Our President

Dr. Phil McDonald is an author, speaker and since 2004, the president of Leader Empowerment And Development, Inc. (LEAD). With thirty-five years of work experience in thirty-eight countries, McDonald has helped set up or empower more than 150 overseas development projects on five continents. Projects included hospitals, clinics, orphanages, safe houses, community centers, schools, businesses, farms, plantations, and factories.

Phil earned a Ph.D. in International Education from Michigan State University and specialized in national planning, policy analysis, and development economics. He received a bachelors degree in Social Science from Cedarville University.

Phil’s wife Rebecca is founder and CEO of Women At Risk International, Inc. (WAR), a leader in the fight against human trafficking, with programs in 54 countries. www.warinternational.org. The McDonalds live in Michigan, have four adult children and seven grandchildren.

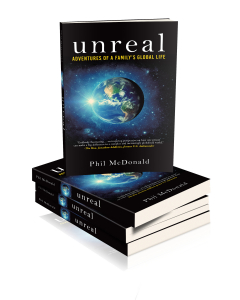

New Book on Social Enterprise

Phil is the author of unreal: Adventures of a Family’s’ Global Life (Northloop Books, June 25, 2019 release, 426 pages) and is available for pre-order at www.pmcdonald.com and www.amazon.com. The foreword is written by the Hon. Jonathan Addleton, former U.S. Ambassador and USAID Mission Director.

Excerpts from the Foreword written by a former U.S. Ambassador

“This is an unusual, informative, and endlessly fascinating book, offering the reader an enjoyable and ultimately inspiring perspective on how one person can make a big difference in a complex and increasingly globalized world. . . .”

“He also provides important insights into his own decision-making process, one in which he repeatedly took the ‘less traveled path’ path. For example, early on he chose to work at a grassroots level rather than enter the highly paid world of the development bureaucracy. In doing so he forged close and enduring personal friendships with a variety of people from all walks of life and all parts of the world, contributing to the rich and revealing set of stories that recur throughout this narrative.”

“Most notably, this book combines the personal with the professional in an unusually effective way, capturing both the external adventure of a life well lived with the internal reflections that were also part of Phil’s life work. The interplay between that ‘inner journey’ and ‘outer journey’ makes for a powerful narrative, at times implicitly encouraging the reader towards similar introspection of their own.”

The Hon. Jonathan Addleton, Ph.D., former U.S. Ambassador to Mongolia and former USAID Mission Director in India, Pakistan, Cambodia, and Central Asia

From the back cover of unreal

“One more thing the captain said. If the pirates get to us, don’t try to escape by jumping into the sea. The waters are full of sharks. Better to take your chances with the pirates.”

-Muhammad Akhtar, Bangladeshi Interpreter

Stalked by lions, charged by rhinos, and chased by pirates, Phil McDonald has lived a life of adventure working overseas. Typhoid, malaria, riots, coups, and rebel soldiers were part of normal life. For his children, any day could be a grand field trip.

While unreal might read like a thriller, this memoir is more than an adventure story. The author recounts ninety events, highlights sixty lessons, from over thirty years of experience. The dirty little secret of humanitarian work in the developing world was a sobering discovery—centuries of handouts created enormous dependency that restricted personal growth and destroyed dignity. McDonald began as an overseas professor and now mentors social entrepreneurs.

If you are drawn to adventure, to travel, and what it’s like to raise a family in an amazing environment, enjoy this read. Discover how to navigate danger, manage fear, and cope with loss. Embrace the hope, laugh at the ups and downs, and revel in the extravagant diversity and courage of inspiring partners who will change you forever.

Excerpt from Chapter 22 “A Glimmer of Hope”

A month after returning to the States, I was asked to go back to Sudan. The second trip included a foursome: a retired British surgeon; an American surgeon from Louisiana; the Michigan businessman leading the project; and myself. Our mission was to visit two hospitals in Southern Sudan.

Our chartered bush plane flew us from Kenya to Western Sudan, and along the way, we landed on a desolate landing strip for a restroom stop. While others relieved themselves on the side of the strip, for some dumb reason, I chose to walk on a path into the bush. Almost out of sight, I heard the pilot shout, “Stay on the path!”

“What did you say?” I yelled.

“Stay on the path. There are landmines everywhere.”

I stopped dead in my tracks. Stupid, how could I be so stupid? I knew it was a war zone. Looking down, I decided to get on with my business right in the middle of the path. I gingerly did an about-face and strode precisely in the middle of the curvy path back to the airstrip, one sure step at a time. Gave new meaning to “walking the straight and narrow.”

After more hours in the air, our pilot descended low enough to recognize several villages.

“I’m pretty sure it’s down there,” he said as we listened in our headphones. Our destination was a rebel SPLA hospital. His voice resumed with a determined set of instructions.

“You need to know this is an active war zone. Once we land, you have thirty minutes before wheels up. While I’m waiting for you, I’m a sitting duck, so don’t you dare be late.”

Our plane rolled to a stop at the end of the airstrip. Seconds later, rebel soldiers in a camouflaged military vehicle pulled onto the landing strip. The four of us bolted out of the aircraft, jumped in, and within a minute arrived in a village.

Our vehicle came to a stop beside what looked like three large mud huts joined together. A Sudanese doctor came out dressed in light green scrubs.

“Welcome to our hospital. Please come inside.”

To our amazement, the inside area of the contiguous mud huts was converted into a long operating room, completely enveloped in a rectangle of thick plastic. A wounded soldier was undergoing an operation.

“The Sudanese government bombed all our traditional hospitals, so we were forced to create these bush hospitals, camouflaging them to look like huts from the air,” said the Dinka surgeon.

Like two machine guns, our visiting surgeons asked him medical questions rapid-fire, gaining as much knowledge as possible in twenty minutes. Soldiers interrupted, we jumped into the vehicle and hustled back to our plane. Ready for takeoff, as soon as we closed the door, the pilot raced down the bush strip and lifted off for our return across the Sudanese Sahel.

Halfway across the region, we landed in Rumbek, a town where several NGOs had set up humanitarian efforts, including a small hospital. Our medical team visited the hospital while the pilot and I checked our group into a tented camp close to the airstrip.

Operated by a Kenyan safari company, long-term NGO workers occupied the camp, but a few “hotel” tents were available for foreigners passing through. Each of us had a private safari tent with a wooden deck as a floor. The dining hall tent served fantastic food, and the local workers were well trained.

Before we left the next day, I was assigned by our team to visit the camp owner in Nairobi and find out what it would cost if they set up a similar camp at our hospital site.

Typical of many small businesses in the developing world at that time, the company’s offices were in a house in a nice residential section of Nairobi. The two owners were white Kenyans, of British descent. After exchanging greetings, the owner in charge handed me a brochure.

“We specialize in setting up temporary tent camps in remote places and it’s done quickly. We can set up a camp for a hundred workers set up a camp anywhere in Africa in two weeks, complete with food service, showers, latrines, and security. What can we do for you?”

“We are planning on building a hospital near the Nile in South Sudan,” I said.

The price quotes were ridiculously expensive, and I pivoted to my main concern, how a hospital in South Sudan could be locally sustainable. The other owner spoke up.

“I think you are missing something here. You are assuming peace will come and an economy will grow. I’ve lived my whole life in East Africa, and the war in Sudan has been going on for decades. There’s no local economy because all the men are fighting, and the women and children are herding cows. When a cease-fire comes, local markets begin to take root, and then the U.N. planes, the “big birds in the sky,” as the Sudanese call them, drop tons of food.”

“What happens then?” I asked.

“The local markets collapse from the huge oversupply of relief food and goods. We’ve seen this cycle time and time again, so it’s unreasonable to expect a hospital to support itself without outside funds. In a war zone, there simply isn’t an economy around long enough to sustain a hospital.”

The man was right. My assumptions were wrong. My Uzbekistan team made the same mistake, believing a change from a centrally planned economy would result in a robust market economy. In reality, the economy in Uzbekistan got worse, not better.

But here I was, the overly optimistic entrepreneur assuming the situation in southern Sudan would get better. I had overlooked a core premise of development economics. The businessman’s distinction between a war zone and a normal third-world economy made perfect sense.

My assumptions about a hospital in a war zone becoming sustainable were incorrect. Sustainability works when there is a semblance of a working economy, where local people have a standard of living capable of paying for goods and services, such as medical care.

PRINCIPLE # 41: “Get it right”

Wrong beliefs and assumptions at the beginning of a project can destroy any chance of success. It’s easy to get caught up with all the opportunity and overlook risks.

The overnight flight from Nairobi to Bangladesh arrived a day before I was to participate in a graduation ceremony at Dr. Bipul’s school. I spent the day amazed at what Dr. Bipul had accomplished in the decade since I left. He set up a college to beef up the English proficiency of the students before entering his graduate school.

Outside of Chittagong, Dr. Bipul also started primary schools in remote areas as well as an orphanage and primary school in his city compound. His compound’s buildings had doubled, and best of all, he did it all on his own. He was a nonprofit entrepreneur, starting new programs as needs arose.

PRINCIPLE # 42: “What is a nonprofit entrepreneur?”

Just like a for-profit entrepreneur builds a business by finding a need for a product or service in the marketplace, a nonprofit entrepreneur starts a program based on a social need in society.

That evening, after a famously delicious meal by Dr. Bipul’s cook, our conversation over a cup of tea in the drawing room was interrupted by the darwan. A guest downstairs wanted to see me, a Muslim woman no less.

I followed the night watchman down the outside stairs and walked out to the gate. Standing there was an elegantly dressed woman in a beautiful green sari, standing by a car, not wearing a veiled burka. In addition to her driver, a bodyguard was also present.

The area near the gate was dimly lit, and I had difficulty seeing her face. But as soon as she greeted me I recognized her voice—it was Amira, my kids’ nanny, for whom we bought the sewing machine to make and sell Shari blouses.

Once a shy, timid woman, she now stood tall and addressed me with confidence. Fortunately, I remembered enough Bengali to carry on a conversation.

“I want to thank you and Memsahib (Rebecca) for helping me buy a sewing machine. I now own a tailoring business and specialize in embroidery. I have employees and own a house. I also own rice paddy land that I rent out. My children are receiving a fine education. Allah has been good to me.”

I was overwhelmed. Beaming with pride, Amira handed me an expensive gift for my wife. Even though we were surrounded by other men, the longer we talked, the more awkward it became. Although she was surrounded by chaperones, a married Muslim woman shouldn’t be talking to a foreign married man, especially in the shadows of the night. We hastily briefed each other on our families before saying farewell.

I walked alone up the stairs and realized you couldn’t manufacture dignity. When you empower a person, dignity naturally follows. She wasn’t the same person I knew ten years earlier. My initial surprise of seeing her and hearing her success, now had turned into joy. I couldn’t stop smiling.

PRINCIPLE # 43: “You go, girl”

Economic transformation for a disadvantaged person not only removes personal risk but replaces it with worth and dignity. And you can’t buy dignity; it’s earned by the one empowered.

The trip to Sudan and Bangladesh was a tonic that soothed my soul. The entrepreneurial growth in Dr. Bipul’s nonprofit organization and Amira’s for-profit business was rewarding to see. I couldn’t wait to return home and share with Rebecca how we played a small part in launching their successes a decade earlier.

On the long flight home, I again reflected on my career options. With our children’s continuing health problems, I knew we couldn’t move back overseas. If we stayed in America, it meant either college teaching or working in a corporate executive position. Neither appealed to me.

Before giving up our relations with donors developed over the years, Rebecca and I met with most of them, explaining our career situation. One man, in particular, made an insightful comment.

“I don’t care what you do next, but if you stay in international work, you should land in a position where you can maximize on all your years of training and experience. What you do is unique, so you should leverage that.”

In time, it became apparent we needed to do just that. Rebecca and I should leverage our experience and put into practice our desire to empower entrepreneurs in developing societies.

Nate and Dani were actively engaged in sports and music in their middle school, had friends, and settled into their routines. The thought of uprooting them again was sickening. I either needed to organize a new nonprofit organization or take a position as a leader in a local one.

Rebecca picked me up at the airport. I briefed her on my trip and then she filled me in on a potential new job.

“He called again,” Rebecca said.

“Who called?” I asked.

“Frank. He needs to retire and wants to recommend you to his board as his replacement.”

Frank, a former youth camp director, had already retired once and lived in our hometown. Restless with retirement, he started a nonprofit organization to bring leaders from Myanmar to America for master’s and doctoral degrees. I knew two of the five who came for their degrees and was impressed all five families returned to their country.

Frank’s little nonprofit wasn’t even a mom and pop organization. It was only him, with no staff, no office, and not even much of a budget, because most of his funding came from himself. By then, I had incorporated or registered over a dozen business or nonprofit entities around the world and could easily have done it again in America.

But Frank already had registered and set up a nonprofit, complete with an excellent board of directors, some I had known since college. I knew from experience that putting a good board together was a hard thing to do, especially finding the right mix of expertise and personalities.

Frank’s board interviewed me a couple of times, made an offer, and I accepted. With a mixture of relief and regret, in September of 2004 I ended my relationship with the old NGO.

The doorbell rang. I opened the door. There stood Frank, a tall, strapping, seventy-eight-year-old man. He held a cardboard box of files, software, a few manuals, and a checkbook. He smiled as he gave it to me.

“Here is your organization,” he grinned.

“So, what are you going to do now?’ I asked.

“You know my wife has terminal cancer, so we sold our home and are moving to Florida.”

“When are you moving?”

“Today.”

Anxious to leave, he didn’t stay long. I shook his hand, thanked him, and said goodbye. I closed the door and set the box down on our kitchen island. Rebecca came into the room.

“That’s it?” she asked.

“Yep, here it is.”

“It’s funny. Compared to our old organization, this is a tiny thing.”

I chuckled, knowing I had resigned from a large nonprofit that raised sixty million dollars a year. With American personnel in eighty countries, they were supported by a hundred headquarters staff. The finance department processed 9,000 donation checks a month.

I set the box on the dining room table and began to leaf through its contents.

“Here’s what’s happened to us,” she said with a twinkle in her eye. “We left the ocean liner for a rowboat. But we’ve grown things before and we can do it again. It’s you and me, baby. I love it!”

Just as Dr. Bipul set himself free from the old nonprofit with its colonialism, outdated methods, and old-school thinking, we had just liberated ourselves from the same institution.

As entrepreneurs, Rebecca and I were excited to finally build an overseas program without worrying about arcane rules and policies that controlled our lives for twenty-one years.

My new little “NGO in a box” did have a problem. It didn’t have any money. Time was of the essence. A letter immediately went out informing our friends and donors about our transition. Although Rebecca and I took a step of faith, I would be lying if I said I wasn’t anxious about the lack of money. We wanted to do big things in remote lands, and that would need sufficient startup capital.

My official start date for leading the “nonprofit in a box” came on a sunny fall day. The woods surrounding our house were alive in color. Leaves from red oaks and yellow maples glided to the ground. A slight wind gently pressed and pulled each leaf without making a sound.

In perfect silence, I walked down the quarter mile paved lane between two rows of tall, green spruce trees. At the end of the lane, I checked our new mailbox on the side of the country road.

On my stroll back, I opened a letter from a loyal friend. All it said was, “Congratulations on your new position. Here is something to get you started. Use it for economic development overseas and go build some sustainable programs!”

Enclosed was a check for $300,000.